- Home

- Brita Sandstrom

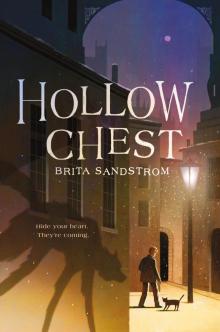

Hollow Chest

Hollow Chest Read online

Dedication

For Mom. Obviously.

Epigraph

i carry your heart with me(i carry it in

my heart)

—E. E. Cummings

In the beginning, there was Hunger, which grew teeth.

There is no other story but this.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

THE SCREAM OF THE AIR RAID SIREN CUT OFF abruptly when Charlie opened his eyes, like a hand had come down to strangle it. The same old nightmare—sirens, dust, the hazy beams of camping torches in the dark—evaporated like smoke and left Charlie in his bed, pajamas damp with cold sweat. A stitch in his chest wouldn’t let him catch his breath, as if he had been running too fast and his lungs had seized up in protest.

He saw for the briefest moment a great yellow eye looking down at him from overhead, burning and burning, before the indistinct shape sorted itself out into a streetlamp outside his window. He let out a slow, shallow breath, his side still hitching.

He felt for Biscuits blindly in the dim morning light, and she made an inconvenienced sound when his fingers sank gratefully into her warm fur.

He was safe. He was home, in bed, where he belonged, his cat tucked against his side. They were safe.

The air raid shelter was gone. The bombs were gone. The war itself was all but gone, finished, over. And yes, his big brother was still gone, but soon—so soon, one week and twelve-odd hours soon—Theo would be just like Charlie and Biscuits, at home in his own bed and safe as houses.

Somewhere outside, a dog sounded, toneless and droning, more of a wail than a howl, really. That was why he’d had the nightmare. Instead of a silly old dog’s howl, he’d heard an air raid siren, and his sleeping mind had tried to protect him as best it could by putting him back into the depths of the Goodge Street shelter during the Blitz, sweating in the dark with too many other people and no Biscuits—

No. That time was gone. He would not think of it. He would not go back.

He stroked his cat’s soft fur again and Biscuits purred groggily.

Safe as houses.

Charlie dressed as quickly as possible, stripping off his sweat-soaked pajamas and shivering his way into a too-big shirt and an itchy wool jumper. It was a bitterly cold London morning outside, and it was only a bit better inside. Grandpa Fitz must have forgotten to get the woodstove going. And if he had forgotten, it was because he was having a bad day.

He swatted down the part of himself that wanted to sigh. Grandpa Fitz didn’t ask to have bad days any more than Charlie asked to have a brother off fighting a war, any more than Charlie asked to have nightmares rather than simple, uncomplicated dreams. Some things couldn’t be helped, they could only be dealt with.

But first things first. Charlie went to the wall calendar, the one that Mum had won at a raffle that displayed pictures of prizewinning vegetables. “February 1945” was spelled in fancy script over an alarmingly large squash. He picked up the pencil hanging next to it and carefully crossed off another day with a big, definitive X. Only one week’s worth of boxes now stood between the Xs and the date circled in red with “Theo Comes Home!” written in Charlie’s very best lettering. Taking a deep, steadying breath, Charlie rolled up his sleeves and went to show the woodstove who was in charge in this house.

The stove was unimpressed by Charlie’s claim of authority, and by the time he had used up almost all their entire remaining firewood to coax it into a cheerful blaze, the sun was nudging itself over the horizon and just beginning to paint London bright as a spring day, despite the snow on the ground. It was a trick, of course. It was always colder than it looked outside these days.

“Jumping Jehoshaphat, it’s cold down here,” Mum said around the several hairpins held in her teeth. As she raced down the stairs, she yanked out curlers with one hand and fussed with her shirt collar with the other. “Dad, I cannot be late again—” She caught sight of Charlie closing up the woodstove and sighed. “Ah. One of those days, is it?”

Charlie nodded bleakly and rubbed at his gritty eyes.

Mum squinted at him and changed course from the teacup cupboard to Charlie, sticking the pins in her hair with mathematical precision. “Bad dreams again?”

Charlie nodded once more, not looking at her. It felt like letting her down, somehow, to still be scared of things long since over. To give her one more thing to worry about.

“Anything I can do?” she asked. A look of worry, fast as a blink, came over Mum’s face, carving a line between her eyebrows that hadn’t been there even a few months before, Charlie was almost sure of it.

“It’s fine, Mum. It’s nothing.” He worked his voice into something resembling cheerful, even if it was still croaky with sleep.

“Was it about your brother?”

“It’s fine.”

Mum looked as if she wanted to say more—Eleven is too young to be such an old man, Charles was a favorite of hers—but she swallowed down the words and ran her hand over his staticky hair. Her eyes caught something behind his head and went huge.

“Is that the time?” That flash of worry again, that line between her eyebrows. “I’m going to miss that infernal bus—” Whatever else she was going to say was muffled by the toast she jammed into her mouth as she flew about looking for her coat and hat, which were hanging on the same peg by the door that they always were every day since forever.

“Have to run, love you, darling!” she called over her shoulder as she threw open the door and dashed out.

“Watch out for the ice,” Charlie called after her. Visions of Mum’s heels flying out from under her and sending her sprawling in the street rushed up at him, the sirens still echoing in his ears. But Mum was already around the corner and out of sight, sure-footed and unafraid.

Charlie squeezed his eyes shut until they hurt a bit, then stood up straight and walked upstairs to Grandpa Fitz’s room.

Grandpa Fitz was sitting up in bed in his striped pajamas, looking at the low-lying sun through his gauzy window curtains. His left sleeve had come unpinned in the night, and he was rubbing the cuff back and forth between his fingers without looking at it.

It was like this sometimes. Grandpa Fitz would go away for a few minutes or hours or even a day, and in the place where he went, he still had his left arm and sometimes Charlie’s dad was alive, or Grandma Lily, or Grandpa Fitz’s first dog, Duck. It still made Charlie cry sometimes—that Grandpa Fitz was able to forget that he’d lost so very many people. And maybe Charlie was a little jealous, too. One day, maybe, Charlie would be old enough to go away like that for a little while and visit Dad, just for an hour or two. That would be nice.

If you’re that old, Grandpa Fitz will be gone, too. So will Mum, so will�

�

Charlie slammed the door on the thought before it could finish. He would not think about it.

He rolled up Grandpa Fitz’s loose sleeve and pinned it in place—when he was back to himself, Grandpa Fitz always hated having his sleeves “flop about like a sailor on leave, up to no good and dragging through the jam.” Then he blew on the cup of tea he’d brought to make sure it was cool enough before holding it up to his grandfather’s lips. Grandpa Fitz’s whiskers glinted in the sunlight, but there was no help for that right now. Charlie did not have sufficient skill to shave Grandpa Fitz’s chin for him. Theo hadn’t, either, but he would always make a great production of pretending to be a barber and putting a hot towel on Grandpa Fitz’s face and putting on and wiping off the thick shaving cream so they at least felt that they had done something.

He pulled Grandpa Fitz’s housecoat on over his right arm and his broad shoulders, still strong as stone even if they were getting slightly stooped. Charlie got embarrassed when he had to dress Grandpa Fitz, even though Theo had never so much as batted an eyelash at helping their grandfather into his trousers and shirt if need be, but Theo was also much taller and stronger than Charlie. He could help in ways Charlie just couldn’t.

But still. When Theo left to fight in the war a year and a half ago, Charlie had promised that he would look after the family while he was gone, that he wouldn’t let Theo down, and he had kept that promise. Charlie had even convinced his mother to let him leave school for a while when Grandpa Fitz had started having so many down days so that he could look after him, at least until Theo returned.

Soon, the bright little ball of anxiety in the center of his guts whispered, so soon.

“I have to go to the grocer’s to get things for lunch, but I’ll be back in just a bit,” Charlie said.

Grandpa Fitz didn’t respond, but Charlie hadn’t expected him to. He simply stared out the window at the dim sky as Charlie gently closed the door behind him.

He stood in the hall biting his lip for a long moment. There were things Charlie should be doing, the endless list of tasks and errands that cost just a little bit too much money, but for five minutes Charlie could ignore them. Just five minutes.

He went back into his room and got down on his hands and knees to reach under his bed, his fingers searching in the dark. Then he pulled the box out from under his bed. It was covered in a layer of dust and a generous coating of cat fur, but he could still see the outline of his fingers from the last time he’d pulled it out.

The letters inside were already starting to yellow, even though they weren’t all that old. The very first one had a picture of Theo’s unit in their long, dark coats and round helmets.

Dear Charlie—I’ll always find you, but can you find me? (A hint: I’m the only one of these grumps smiling.)

Sure enough, all of them looked remarkably identical, but Theo was in the second-to-last row, third from the left. Charlie had circled him in pen, just to make sure Theo knew that Charlie had found him.

The letters went on:

Dear Charlie—Thanks a ton for your letters, I’ve been reading them to the boys who haven’t been getting any from home (I knew you wouldn’t mind me sharing them). Your account of the Great Christmas Story Reenactment Disaster of ’43 was a big hit with the lads. In Biscuits’s defense, no one can really prove there was NOT a cat present at the birth of Christ, so Father MacIntosh really shouldn’t have got so worked up about it.

Dear Charlie—The army is very keen on running and jumping about, and I feel I must thank you for all those snowball fights, as they were a great preparation for basic training.

Dear Charlie—Greetings from the picturesque French countryside! At least, I imagine it is picturesque, as all we see are the insides of our tents.

Dear Charlie—Nothing much to report. Thank you for the letters. The weather is nice today, which makes for a change. Sorry to become one of those people who talk about the weather. Still, I hope the weather is nicer where you are. I hope the weather is perfect for you today. What else could I tell you, that you would want to know? Maybe it’s best to stick to the weather for now. I can tell you the shapes I saw in the clouds through the window I’m stuck in front of: a cat, a crown, a sword, a wolf, a pie, a bed, another bed. Sorry, not my best.

Theo

Dear Charlie—I might not be able to write for a while, didn’t want you and Mum to worry.

Dear Charlie—Happy birthday. T.

The letters had dwindled and winnowed and withered down to one postcard from Paris that had only had Theo’s signature on it with no note.

And then the horrible one that Mum had wept over.

Dear Mrs. Merriweather,

It is with great regret that we must inform you that your son, THEODORE FITZWILLIAM MERRIWEATHER, was injured in the line of duty. He is currently receiving medical care at L’HÔPITAL DE SAINTE MARIE. He will be granted a MEDICAL LEAVE no later than February 10.

Yours sincerely,

Gen. C. Marshal Greene

And after that—nothing.

Why had he stopped writing? Because he was too hurt to write?

No. Charlie put the thought into a box and locked it and threw it away.

Perhaps Theo was too busy, or doing something top secret that was strictly need-to-know for the government. Or maybe the hospital he was recovering at was so far off the beaten path that mail carriers could only get there by foot. Maybe there was a whole heap of letters that he’d sent but that had gone astray, or the mail train had been hit by a bomb, or there was someone else named Charlie Merriweather in another city who kept getting his mail by mistake and was very confused by the exploits of this Theo character.

But Theo was alive. He was coming home. There was an explanation, and soon (so soon!) Theo would be able to tell him.

There were two more things at the very bottom of the box. The first was a photograph, and Charlie almost didn’t look at it. But it drew him like a magnet, like it was hooked to something inside him and tugging. It was the picture of Mum and Dad on their wedding day, both of them trying so hard not to smile or move for the camera that they looked rather cross for having just gotten married. It was before Dad had a beard, and Mum’s hair was much shorter and curled. Charlie’s finger hovered over Dad’s face, afraid to touch the photo for fear of wearing it, as he tried to match the face in the photo to his memories of him. But Dad’s beard and gray-streaked hair and weathered skin in Charlie’s head were at odds with the stern jaw and dark hair and grim expression in the photo. Charlie couldn’t really remember Dad that well anymore, except for a few bright shards of memory that gleamed and cut like glass. But that was a secret he kept from everyone but Biscuits, to whom he would recite everything he could remember about Dad into her fur sometimes at night. His big hands, his pipe-smoke smell, his scratchy wool jumpers, his gray-streaked brown hair.

And lastly, underneath the picture, was a bit of scratch paper with a list of things to get at the chemist’s in Dad’s inelegant, squarish writing. Charlie held the paper with both hands, mouthing each word silently—tea, sugar, aspirin, iron tablets, peg hooks.

He squeezed his eyes shut and drew in thin, shaky breaths.

“Theo will be home soon,” he said out loud in a snuffly whisper. “He’ll be home next week.”

Out in the hall, Biscuits was awake and crying for him. Charlie wiped his face with his sleeve and opened the door.

2

BISCUITS WAS DEMANDING HER BREAKFAST, yowling in a plaintive voice and pawing at his leg with big, accusatory eyes. His cat was, in Charlie’s opinion, a perfect specimen of her kind, exactly everything a cat should be: small and fine-boned with delicate triangle ears and soft, downy white fur with artfully arranged marmalade-colored patches for contrast.

“When have I ever let you starve?” Charlie demanded, bending down to rub her little ears the way she liked. But Biscuits refused to be distracted from her imminent starvation and flung herself onto the ground, languishing. C

harlie dumped a small pile of kitchen scraps into her special bowl from a big container he had bought specially to keep them fresh in the icebox (and the mice out of them). But she abandoned her breakfast after just a few bites when she realized he was leaving, sneaking past his legs and out the door.

She meowed a greeting to Sean O’Leary, who was just finishing up shoveling the walk to his house. Sean and his family had lived two doors down from the Merriweathers for as long as Charlie could remember. They were in the same class at school, back when they both went to school. Like Charlie with Grandpa Fitz, Sean had been out of school for the past few months, helping take care of his younger brothers and sisters so his mum could work. He was probably Charlie’s closest friend, at least since so many of the other kids had been sent away into the country to wait out the war. Mum had flatly refused to send Charlie and Theo away from home—she and one of the other mums at church had had a politely vicious row about it. “Only God is going to separate this family again,” Mum had said, in a voice he had never heard her use before, or since. Mrs. Lancaster still scuttled away from her whenever they made eye contact over the church biscuits.

“Do you fancy going down to the shops after this?” said Sean, brandishing his shovel. “I’ve got to pick up some stuff for my mum, so I’m taking the bicycle.”

Charlie raised his eyebrows, impressed. The O’Leary bicycle was in high demand. Sean was the middle of six kids, and he always seemed to be corralling a small herd of younger siblings like a long-suffering sheepdog. It always made Charlie smile to look at Sean, because he could see already exactly what Sean was going to look like as an old man: patient but almost permanently a bit exasperated.

“I can’t,” Charlie sighed. “I have to go to the grocer’s for Mum. Grandpa Fitz isn’t up to it today.”

Sean nodded. Charlie didn’t share with him everything about Grandpa Fitz’s bad days, but he had enough of a general impression to mind his business. Minding Your Business was gospel in the O’Leary house, second only to the actual Gospel. It made Sean a rather useless friend to gossip with, but more and more lately, Charlie had begun to appreciate it.

Hollow Chest

Hollow Chest